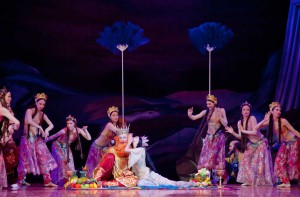

Andris Liepa has always brought us interesting productions, but his partnership with Georgi Isaakian and the Natalia Sats Moscow State Musical Academic Children’s Theatre seems to have enabled him (and us) to travel back in time. Almost 100 years to the day since it was first performed in London, we were treated to the rare and ravishing spectacle of the full opera/ballet with recreated Goncharova sets and glorious hand-painted costumes. It cannot have been seen like this since its inception. The colours and patterns seem childlike but also reach into a deep Russian history that is reflected in enamel boxes, Matrioshka art and, oddly, in the plain strips and blocks of Malievich or the flying figures of Chagall. It is worth visiting to view the craftsmanship alone. Gorgeous vibrant colours burst out like leaves from an exotic pop-up book. The opening cloth, a William Morris-esque foliage pattern was slowly illuminated from the stage up, turning blues and sage greens into blushing pink. Two gobos rotated to create a kaleidoscope effect that drew the eye, the imagination and the heart into the world of Tsar Dodon and the golden cockerel. This is gesamkunstwerk at it very finest: dancers, singers and musicians meld into one until it seems that dancers sing – and oh, what singing! Pushkin’s tale springs to life, every word as clear as a bell, the richness of the Russian resonating and seemingly animating the dancers. Dimitry Pochapsky as Dodon could have been Chaliapin resurrected. Petyr Melentiev’s Astrologer soared to the heights of an alto with perfect intonation. But the superstar in this firmament was undoubtedly Olyesa Titenko as the Queen of Shamakha. Russia has always produced sopranos with limpid voices and Titenko could hold her own with the very best in the world. Her coloratura was pitched at just the right level, effortless rather than showy, with a top C that sprung from nowhere and landed dead in the middle of the note. Titenko is a stunning presence and a generous performer who could easily have stolen the stage but who kept her performance at exactly the right level to serve the production. Mention too should be made of Natalia Eliseeva’s housekeeper, a true contralto.  ‘Le Coq d’Or’, here with Daria Liakisheva as the Queen of Shemakha and Oleg Fomin as Tsar Dodon. Photo © Elena Lapina Although painstaking research has unearthed and re-created original designs, Fokine’s choreography is lost. What we see here is then a tribute to his innovation and it works well. Movement is always in service to character and narrative, but the trap of merely miming to the singers is avoided. There are some fiendish sequences, not least for the eponymous cockerel (Pavel Okunev) who, like the Golden Idol in “La Bayadère”, explodes onto the stage with every entrance. Choreography often works against the music as the characters drive the movement. There are stamps and folk dance-inspired flexed feet, but plenty of classicism too. Natalia Savalieva’s Queen of Shamakha has fluid lines and sinuous extensions. She is both seductress and ephemeral sprite, a fleet will-o-the-wisp that finally disappears like a plume of smoke, only Titenko’s vindictive laugh echoing in her wake. Oleg Fumin’s Dodon is a masterpiece. Without the obvious showiness of the cockerel and with no large set pieces, he nevertheless creates an impressive Tsar. It is easy to believe that he has authority but also that he is a prize fool, led by his base desires and oblivious to the entreaties of his sensible housekeeper. Resplendent in orange wig and cloak, he is a sensitive partner with a mastery of technique that enables him to project character at every turn. He is well matched by the lithe Maksim Podshivalenko as the Astrologer who, from the outset, is given challenging steps to which he proves more than equal. One of the most entrancing scenes was left to Pochapsky and Titenko, alone on stage, as they weave a love duet with Shemakha’s scarf (also sported by Savalieva). The scarf has a long history of symbolism in the ballet, especially in the Romantic era, and often represents the ephemeral connection between the supernatural and the mortal world. Here, it also unites singer and dancer so that one naturally accepts that they are one and the same.

‘Le Coq d’Or’, here with Daria Liakisheva as the Queen of Shemakha and Oleg Fomin as Tsar Dodon. Photo © Elena Lapina Although painstaking research has unearthed and re-created original designs, Fokine’s choreography is lost. What we see here is then a tribute to his innovation and it works well. Movement is always in service to character and narrative, but the trap of merely miming to the singers is avoided. There are some fiendish sequences, not least for the eponymous cockerel (Pavel Okunev) who, like the Golden Idol in “La Bayadère”, explodes onto the stage with every entrance. Choreography often works against the music as the characters drive the movement. There are stamps and folk dance-inspired flexed feet, but plenty of classicism too. Natalia Savalieva’s Queen of Shamakha has fluid lines and sinuous extensions. She is both seductress and ephemeral sprite, a fleet will-o-the-wisp that finally disappears like a plume of smoke, only Titenko’s vindictive laugh echoing in her wake. Oleg Fumin’s Dodon is a masterpiece. Without the obvious showiness of the cockerel and with no large set pieces, he nevertheless creates an impressive Tsar. It is easy to believe that he has authority but also that he is a prize fool, led by his base desires and oblivious to the entreaties of his sensible housekeeper. Resplendent in orange wig and cloak, he is a sensitive partner with a mastery of technique that enables him to project character at every turn. He is well matched by the lithe Maksim Podshivalenko as the Astrologer who, from the outset, is given challenging steps to which he proves more than equal. One of the most entrancing scenes was left to Pochapsky and Titenko, alone on stage, as they weave a love duet with Shemakha’s scarf (also sported by Savalieva). The scarf has a long history of symbolism in the ballet, especially in the Romantic era, and often represents the ephemeral connection between the supernatural and the mortal world. Here, it also unites singer and dancer so that one naturally accepts that they are one and the same.  The fairy-tale world is however a mask for the biting satire of a production created just two years after the first Russian Revolution and in the wake of the disastrous Russo-Japanese war, the main target of its parody. Shemakha represents the orient, a target for Russian empirical expansion, and Dodon’s greed reflects a Tsar who indulged in Faberge trinkets while brutally supressing dissent and presiding over a country with huge extremes of wealth and poverty. It is easy to see why it was censored and first presented to Paris and London by a company in exile. That is has largely been ignored since is an artistic crime, but oh how privileged we are to be here at its revival. Diaghilev and many of his dancers spent the majority of their lives far from their homeland. With this production, Liepa and Isaakian have enabled them to come home. by Charlotte Kasner photographs by Elena Lapina Critical Dance

The fairy-tale world is however a mask for the biting satire of a production created just two years after the first Russian Revolution and in the wake of the disastrous Russo-Japanese war, the main target of its parody. Shemakha represents the orient, a target for Russian empirical expansion, and Dodon’s greed reflects a Tsar who indulged in Faberge trinkets while brutally supressing dissent and presiding over a country with huge extremes of wealth and poverty. It is easy to see why it was censored and first presented to Paris and London by a company in exile. That is has largely been ignored since is an artistic crime, but oh how privileged we are to be here at its revival. Diaghilev and many of his dancers spent the majority of their lives far from their homeland. With this production, Liepa and Isaakian have enabled them to come home. by Charlotte Kasner photographs by Elena Lapina Critical Dance