Reviewed by Graham Watts – Wednesday 17 July 2013

Performance reviewed: 16 July

Hot on the heels of one Muscovite ballet company (the Stanislavsky) departing the London Coliseum, another arrives; since Andris Liepa’s Russian Seasons programme is constructed around the company that performs at the vast 6,000 seat State Kremlin Palace in the heart of Moscow, just a hefty stone’s throw away from the Bolshoi theatre and its famous ballet company, which will shortly be in residence for three weeks at the Royal Opera House. Uniquely, in the space of a fortnight, all three of Moscow’s big ballet companies will have performed in London.

The Kremlin Ballet is a hard-working company that tours the world as well as maintaining home seasons for a knowledgeable Muscovite audience. It has been directed since 1990 (its whole life) by former Bolshoi soloist, Andrei Petrov, and in recent years has broadened both its repertoire (Wayne Eagling’s Beauty and the Beast is a recent addition) and its horizons (enjoying, for example, a month-long winter season in Athens for the past two years). But, despite performing in the biggest theatre in Europe (regularly filled to capacity) and attracting world class guests (Vadim Muntagirov, Daria Klimentová, Tamara Rojo, Alina Somova, Johan Kobborg and Alina Cojocaru have all performed with Kremlin Ballet since 2011) it remains very much in the shadow of the big beast at the Bolshoi and the emerging giant of the Stanislavsky.

It is a pity, therefore, that the Kremlin Ballet is overshadowed in the credit for this particular season at the Coliseum. There is no printed programme for the event but the cast sheets handed out instead make no reference whatsoever to the company that provides the basis for the performance (and all but three of the dancers). At least Mr Petrov got to share in the final curtain calls.

The person who appeared most on stage was the show’s producer/director, Andris Liepa, a former Bolshoi principal and part of a major soviet-Russian dance family, who – perhaps in the absence of a printed programme – came on stage before each piece to explain its history and who was dancing. His first appearance was to apologise for the fact that an injury to his sister, Ilze Liepa, meant that the much-anticipated reworking of Cléopâtre – Ida Rubinstein by Patrick de Bana had to be cancelled. Regrettably, this bad luck continued in the gap between the first, short work and The Firebird, when a technical glitch required a few extra unscheduled, impromptu “stand-ups” from our urbane, blonde host and Liepa’s unflappable charm kept an otherwise impatient and over-heated audience on his side.

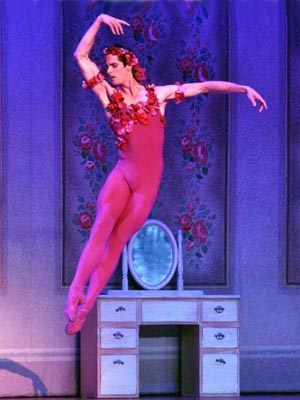

After a while, an extra interval had to be ordained and it must have been a very rare occasion that Le Spectre de la Rose – a 10-minute divertissement – has had a whole act to itself. In this slight but famous work – first presented by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in April 1911 – a girl returns from her first ball and falling asleep in a chair, dreams that the spirit of the rose in her hand has come to life and dances with her. It provided a fascinating opportunity to see former Royal Ballet dancer, Xander Parish, now with the Mariinsky Ballet, dancing as the rose and his was a well-judged, suitably ethereal and lyrically delicate performance. Parish is tall and handsome but with the softness and nobility of a poetic danseur, very much in the mould of Anthony Dowell or, more recently, Roberto Bolle. On this evidence, his emigration to Russia is a huge loss to British ballet and I hope we see him back on the UK with a principal’s contract in his back pocket before too long.

The unscheduled interval was soon forgotten with a colourful performance of Liepa’s excellent The Firebird, superbly led by Alexandra Timofeeva in the title role and the Bolshoi’s Mikhail Lobukhin as the Prince Ivan. I count myself fortunate to have seen Timofeeva dance several times (in Moscow, Athens, Paris and Manila) and the prima ballerina of the Moscow Kremlin company is both an accomplished all-around technician and a consummate performer. After a slightly nervous start, Timofeeva’s Firebird grew in stature and confidence, her eyes lighting up the stage and her fluttering hands in perpetual motion. The scene in which she returns to rescue the prince from the evil Koschei (Igor Pivorovich) was a masterclass of feminine power, precision and charisma. And the production was also greatly helped by Lobukhin’s arresting dramatic skill and projection. Every expression of both principals was as telling as a line of clearly articulated dialogue.

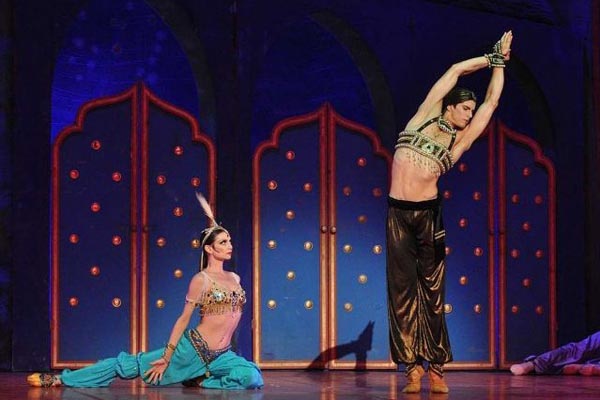

The colour and drama continued into Liepa’s recreation of Mikhail Fokine’s Schéhérazade, with its rich re-interpretation of Rimsky-Korsakov’s score (albeit an arrangement that was denounced by his widow when the ballet was first performed by Diaghilev’s troupe in 1910). It was a pity that all the evening’s wonderful music was blared out of loudspeakers instead of played live but we must all recognise the economic difficulties in engaging a full orchestra for such brief seasons. As with The Firebird, this was a wonderful reliving of history – even the earlier glitches had a kind of authentic charm in keeping with the Diaghilev spirit – enjoying a glorious palette of colours in the diverse array of cartoonish, exotic costumes.

Schéhérazade tells the tale of a forbidden love between the Sultan’s favourite concubine, Zobeide, and the Golden Slave, which is requited in an orgy of lust between the girls of the harem and the Sultan’s slaves once the latter has gone off to hunt. Unfortunately, he and his guards come back in time to catch them all at it and all – including the Golden Slave – are put to the sword. Zobeide is spared but then takes her own life. Once again, Parish impressed as the Golden Slave alongside the Mariinsky’s Yulia Makhalina, now 45 but still incredibly impressive with her high cheekbones and haughty beauty. Makhalina played both the young girl in Spectre and Zobeide in this tragic tale of Schéhérazade. Parish is over 20 years’ her junior but here was yet another example of a younger male dancer enjoying a strong partnership with an older, mature ballerina in a relationship that seems as natural as vodka and caviar blinis. All in all, glitches overlooked, this was a fun programme that I greatly enjoyed.

Graham Watts writes for londondance.com, Dance Tabs, Dancing Times and other magazines and websites in Europe, Japan and the USA. He is Chairman of the Dance Section of the Critics’ Circle in the UK.

Photos: John Ross