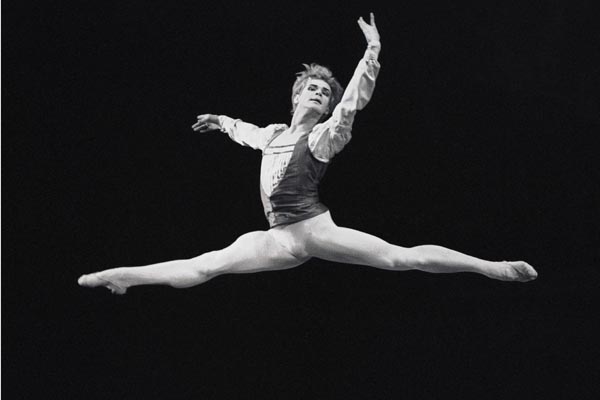

One hundred years on, Andris Liepa, son of famous choreographer Maris Liepa, recreates the performances of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in London.

Vintage stagings of Le Coq d’Or (The Golden Cockerel) and Petrushka arrived in London on July 8-13.

As the premiere approached, Andris Liepa talked with RBTH about the Diaghilev legacy, foreign soloists and why he doesn’t sign political letters.

Russia Beyond the Headlines: Diaghilev’s combination company made its name in France. Why is Russian Seasons (Ballets Russes) being held in London and not Paris?

Andris Liepa: It was in fact in Paris that we organised the premiere of the restored performances – in 2009. But if we recall the history, a century ago, Russian Seasons conquered Berlin and London after Paris. And the London public adored Diaghilev’s troupe. Sergei Diaghilev often performed at Covent Garden and the Coliseum Theatre where we are also to perform.

RBTH: Did you and your father dance on these stages?

AL: Many years ago my father performed the part of Crassus in the ballet Spartacus at the Coliseum, and I visited London for the first time in 1986 as a dancer in a Bolshoi Theatre ballet held at Covent Garden. On subsequent tours with the Mariinsky Theatre I danced at the Coliseum. It has a capacity of 2,300 spectators, which is a lot for a ballet. It is more than the Bolshoi and close to the American Metropolitan. But the most important thing is not scale; rather that Diaghilev himself presented Russian Seasons there. The tour poster from 1926 has even been preserved.

RBTH: And why do the performances need to be restored in general?

AL: Because there is no way to transcribe a ballet, like it is possible to do with music. Music is “stored” in a score and if the score is preserved then the music can be reproduced. Of course, one can interpret pauses, louder or smoother sounds, that is to say give some kind of interpretation to it, but the notes remain the same. It is not the same in ballet, and every subsequent performance becomes less and less like the original. But there are diaries, memoires, sketches, representations, the way it had to be in those years. In 1957, Mikhail Fokine’s son Vitaly returned two huge chests from New York that had materials and domestic recordings of Mikhail Mikhalovich (Fokine) himself in them. He understood that these things were unique and must be preserved somewhere in the motherland. So, imagine, I was then the first person who received these documents according to the form. They had lain there since 1957 and no one had been interested in them.

RBTH: What were the documents?

AL: Sketches and choreographic sketches, for example, for the corps de ballet in Sheherazade. There are many things that are clearly spelled out. In addition, Fokine wrote a large book called Against the Current. There are many recollections about Firebird in it, how he saw that ballet. He dreamed that Firebird would return to Russia. I brought his dream to life in 1993. Until then, there had been no original stagings in the USSR. After the Bolsheviks came to power, they invited Diaghilev to Russia, but he declined, thank God. Otherwise, he simply would not have survived. Many of Fokine’s compatriots, not wanting to leave Russia under Lenin, perished in the dungeons of the NKVD during Stalin’s time.

RBTH: Surely they knew about Russian Seasons in the USSR?

AL: Of course, they were aware that there was some choreographer Fokine that had staged several performances. Les Sylphides was even presented on the stage of the Kirov Theatre; it’s called the Mariinsky Theatre now. It was presented because it had been written especially for it. But they never did anything else. Every Russian that stayed in the West was considered persona non grata – staging the works of “defectors” wasn’t done.

RBTH: But performances forbidden in the USSR were staged for many years in Europe. And foreign soloists often played the parts of Russian heroes. Are there any foreigners in your troupe right now?

AL: Joy Womack. She entered the Bolshoi Theatre and has now come to the Kremlin Ballet. She works on and dances solo parts. The British ambassador is very pleased and comes to her performances. She is a very good girl. There is also one Brit, Xander Parish. He fell in love with Russian ballet. After he finished ballet school in Covent Garden, he worked in the troupe for a year and a half, went on tour, joined the class, and asked to train at the Mariinsky. They accepted him and he truly began to grow. In our Russian Seasons, he dances the part of the Golden Slave in the performance of Sheherazade and he makes such fantastic leaps, like Nijinsky did back then.

RBTH: You talk about the Bolshoi and Mariinsky. No explanation necessary. But what does the Kremlin Ballet mean? You became the artistic director of this theatre a month ago.

AL: At first, the Kremlin Palace stage was the second stage for the Bolshoi Theatre. When I joined the theatre, I worked in the Bolshoi and in the Kremlin Palace of Congresses. Everyone who came from abroad to the Soviet Union ended up at either the Bolshoi or the opera in the Kremlin. Thus people who know even a little about Russian theatre understand that it is a single entity. During perestroika (under Mikhail Gorbachev), it was divided into two directorates; one remained at the Kremlin and the other became the Bolshoi Theatre.

RBTH: “Kremlin” means that the theatre is tied to the Kremlin, doesn’t it? Don’t you worry that you could have some kind of complications in your relations with Western partners, as has happened with some of your colleagues, because of your ‘proximity to power’? Such as what happened with Valery Gergiev in particular?

AL: These complications arose after Gergiev signed an open letter in which he approved of Putin’s policy in relation to Ukraine and the Crimea. I understand that in the West this was traced and pressure was placed abroad specifically on those who signed such a letter. I, although I support such a policy internally, never signed any such paper. My father once said: “Andris, never sign anything.”

RBTH: Judging from your biography, you have never had any conflicts with the authorities. During Gorbachev’s time, you became the first performer who received official permission to work for an extended period in the United States. How did you earn such trust?

AL: It was perestroika, a new period in Russia. In America they even called me the ‘perestroika kid.’ They issued me a Soviet passport with a multi-exit visa. You cannot imagine what that was. During that time they didn’t let you out of the Soviet Union. I mean you couldn’t even leave even if you had a visa in your passport, for example an Italian one, because you didn’t have a Soviet exit visa. But I could just go anywhere without informing anybody.

Read the full story at RBTH